Charting the hydrogen frontier: Kawasaki Heavy Industries

The voyages of certain ships mark the dawn of new eras. History changed when Columbus’s caravels reached the West Indies, Darwin’s HMS Beagle landed on the Galapagos Islands and Commodore Perry’s Black Ships neared Edo. The Suiso Frontier, the world’s first liquefied hydrogen carrier built by Japan’s Kawasaki Heavy Industries (Kawasaki), may be just such a ship, marking a new era of hydrogen energy.

In January 2022, the one-of-a-kind vessel completed its first international voyage to Victoria, Australia. After filling its 1,250m3 tank with hydrogen liquefied at minus 253 degrees centigrade, the ship successfully returned to Kobe, Japan, at the end of February 2022.

Suiso Frontier’s successful return trip is a significant milestone in the global race to establish commercially viable supply chains for hydrogen, which is a ‘clean’ low-carbon alternative energy that emits only water when burned.

“You need all these technologies – from liquefiers, loading systems, storage tanks, trailers and more – to establish a hydrogen supply chain,” explains Motohiko Nishimura, president, Energy Solution & Marine Engineering Company, Kawasaki Heavy Industries. “But the one thing missing in the world until now was a carrier. With the Suiso Frontier, we have demonstrated that liquefied hydrogen can be transported like natural gas for mass use.”

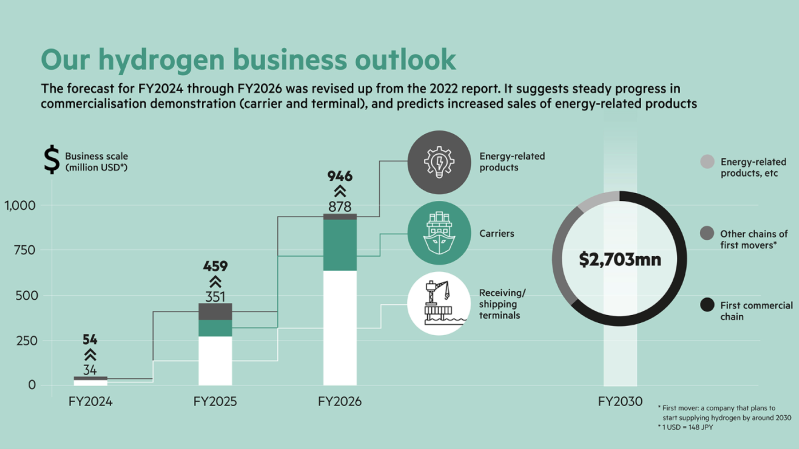

Kawasaki’s latest triumph confirms its place as a key first mover in the emerging hydrogen economy. The news is also a testament to the progress made in accelerating its hydrogen-related businesses, as announced in its long-term strategy, Group Vision 2030. Through this strategy, Kawasaki aims to achieve carbon neutrality with hydrogen and realise a hydrogen society.

Pioneering a hydrogen supply chain

The Suiso Frontier’s journey is part of a pilot project by a consortium of Japanese and Australian companies and backed by their governments to make and transport liquefied hydrogen by sea to an international market at scale. The goal is to demonstrate the technical viability of such a hydrogen supply chain by the late-2020s and aim for commercialisation around 2030. Once in the commercial phase, 225,000 tonnes of liquefied hydrogen will be imported to Japan per year, which will go through further production.

Massively scaling up production, storage and transport volumes will slash costs. Kawasaki is currently developing a hydrogen tanker with a cargo load 128 times that of the Suiso Frontier and a storage tank 32 times larger than its pilot one, to be deployed by mid-decade.

Demand for such hydrogen is growing. According to the Hydrogen Council and consultancy firm McKinsey & Company, the hydrogen market is expected to reach some $2.5tn and generate 30m jobs, while providing 18 per cent of the world’s energy and more than 20 per cent of emissions reduction globally by 2050.

Nishimura expects hydrogen delivered by sea to be particularly vital for densely populated coastal cities in Asia with high energy demands yet inaccessible by pipelines.

“Kawasaki has received many requests from countries around the world to consider hydrogen-related projects,” says Nishimura. “We hope to capture growing demand by being first with a track record in building hydrogen chains.”

Leading in the lightest element

Founded in 1896 as a shipbuilder, Kawasaki is a “technology corporate group” with over 100 group companies globally building ships, rolling stock (including bullet trains and New York City subways), aerospace systems, energy systems, plants, precision machinery, robots and its famous brand of motorcycles.

But the heavy industry giant has also long been involved in the lightest of elements, hydrogen.

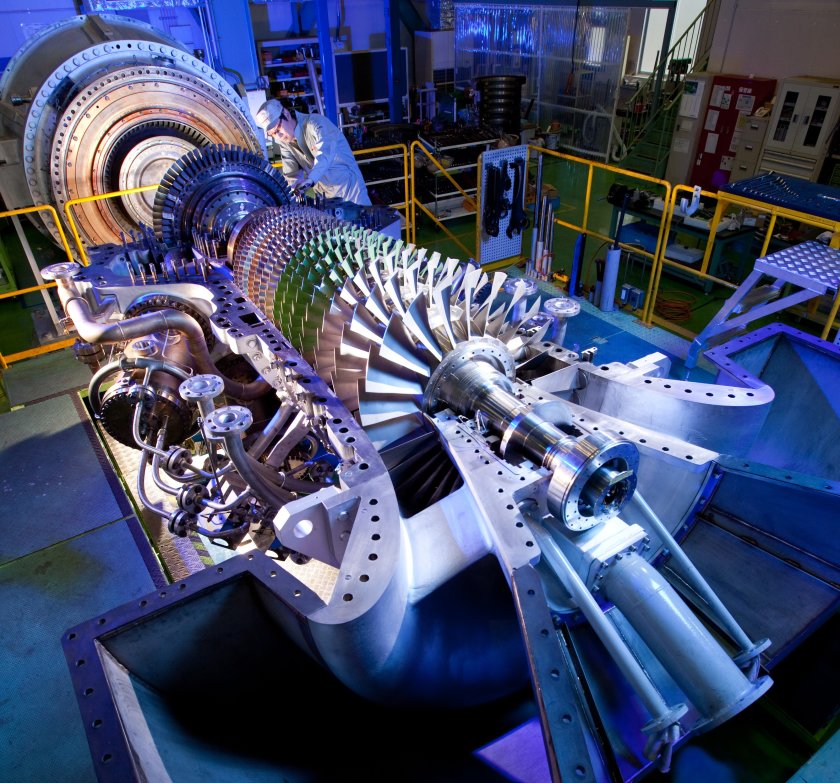

Starting in the 1980s, Kawasaki built liquefied hydrogen storage tanks for the Japanese space agency’s rocket launch facilities. As a leading supplier of LNG tankers, storage facilities and gas turbine engines, Kawasaki has also accumulated know-how in cryogenic fuels.

“We realised that as a conglomerate, our key strength was possessing the core technologies needed to make, carry, transport and store hydrogen all through the supply chain,” says Nishimura. After declaring its intention to create just such a chain in 2010, Kawasaki has pushed for realisation, working together with partners nationally and internationally with the support of the Japanese and Australian governments. The scale of KHI’s hydrogen business is expected to hit ¥400bn ($2.7bn, 1USD= 148 JPY) in 2030.

“We will contribute not only to the utilisation of hydrogen energy technologies globally, but also to the establishment of business models for new services, the development of regulations and the creation of international standards,” says Nishimura. Kawasaki has been central to developing emerging industry standards for liquefied hydrogen tankers and loading arm systems, among other areas.

Contributing beyond the supply chain

Kawasaki is also helping industries reduce their carbon footprint through hydrogen energy use technologies.

Already, it has demonstrated the viability of its hydrogen gas turbine engines, which can burn either pure hydrogen, natural gas, or a mixture as fuel efficiently, safely and cleanly. In 2018, it installed a world-first hydrogen cogeneration system in Kobe city to provide heat and power to the surrounding urban area. The project has been followed by a request from Germany’s RWE Generation to build one of the world’s first 100 per cent hydrogen-capable gas turbines on an industrial scale. The German plant, with an output of 34 MW, could become operational in 2026.

Kawasaki is also moving ahead in developing hydrogen-fueled engines for ships and aeroplanes together with various partners.

Carbon capture and storage (CCS) technologies developed by the Japanese company — involving solid sorbents comprising porous materials, which can separate and capture CO2 using less energy than conventional methods — will also contribute to decarbonisation. Pilot tests of the CCS methods are being conducted in Japanese thermal plants, and commercialisation is expected in the coming decade.

To demonstrate to the world a pathway to carbon neutrality through hydrogen, the company has pledged to achieve net zero carbon emissions of its domestic sites by 2030. It aims to achieve this primarily by adopting its own hydrogen power generation, energy-saving and CCS technologies.

“Now that there is a global consensus over hydrogen as a vital solution to today’s environmental challenges, we hope to contribute to the world by providing safe and optimised solutions across the hydrogen supply chain, which only we can provide,” says Nishimura.

Hydrogen has the potential to revolutionise the clean energy transition. For pioneers such as Kawasaki, blue ocean (and hydrogen) opportunities stretch far into the horizon.

This content was paid for and produced by Kawasaki Heavy Industries in partnership with the Commercial Department of the Financial Times.

![]() Energy and Environment

Energy and Environment![]() Energy and Environment

Energy and Environment