What is needed for hydrogen to really take off?

Yoshinori Kanehana recalls a palpable sense of anticipation in the air during the inaugural meeting of the Hydrogen Council, which launched at the World Economic Forum in Davos in January 2017.

Yoshinori Kanehana recalls a palpable sense of anticipation in the air during the inaugural meeting of the Hydrogen Council, which launched at the World Economic Forum in Davos in January 2017.

“At the time, hydrogen was not widely recognised, so the council’s goal was to promote it as a vital tool for decarbonisation,” says Kanehana, who is chairman of Japanese technology company Kawasaki Heavy Industries (Kawasaki) — one of the founding members of the Hydrogen Council — and also serves as the council’s co-chair.

The Hydrogen Council is a global chief executive-led initiative with a united vision for hydrogen to foster the clean energy transition. Kanehana recalls how the council initially launched with 13 companies from different industries coming together under this shared vision.

“Since Davos in 2017, awareness of hydrogen’s potential has grown massively,” says Kanehana. “Today, the council is composed of nearly 140 leading multinationals from a wide range of industries with a total market capitalisation of $8.2tn.”

As early as 2010, Kawasaki had already unveiled its forward-looking vision of establishing international hydrogen supply chains, recognising the significant potential of hydrogen in the energy transition. Subsequently, the company has been developing and demonstrating technologies necessary for each phase of the supply chain, encompassing hydrogen production, transportation, storage and utilisation.

The Hydrogen Council’s global presence, fostering collaboration among governments, industries and investors, positions it to play a pivotal role in advancing global carbon neutrality through hydrogen.

Thanks to the council’s efforts, coupled with the growing international commitment to combat climate change and the renewed emphasis on a stable energy supply underscored by the Ukraine crisis, interest in hydrogen has never been higher.

Hydrogen, which does not emit carbon dioxide when burned, can be produced stably from a variety of resources found around the world, making hydrogen an effective option from the standpoint of energy diversification. Unlike electricity, liquefied hydrogen can be stored and transported in large quantities over long periods, making it an ideal carrier and storage for renewables. According to the Hydrogen Council, by 2050, hydrogen could contribute to over 20 per cent of the annual global emissions reductions required to achieve global net-zero emissions, particularly for hard-to-abate industries such as steel, heavy-duty transport, shipping and aviation.

The council also reports that more than 1,400 hydrogen projects, equalling $570bn investments, have been announced globally, with 45m tonnes per annum of production announced across low-carbon and renewable hydrogen by 2030.

Of the $570bn direct investments into hydrogen projects announced to date, $40bn have passed final investment decision (FID) — the stage during an infrastructure project where a company decides whether to move forward or not — and the rest are expected to follow by 2030.

However, there remains an investment gap of $430 billion for the world to meet the 2030 target.

To close this gap, a further push is needed.

Offtake agreements and government incentives for hydrogen

“It’s a classic chicken and egg situation: hydrogen producers need guaranteed buyers, while buyers need guarantees of steady supply if both are to commit the capital investments necessary to develop hydrogen,” says Kanehana.

The Hydrogen Council believes that for developers to make FID, securing long-term offtake agreements and government funding is vital. Of the 370 hydrogen projects that have achieved FID (which include large-scale industrial use, mobility and giga-scale hydrogen production projects) most have demand secured in the long term, either internally or through offtake contracts.

Behind many of these finalised hydrogen projects are government incentives and schemes that give buyers certainty about the availability and affordability of clean hydrogen over time. This synergy is being achieved by government policies that help bridge the price difference between clean hydrogen and alternative fuels. For developers, government backing across various stages of development allows them to step up volume, achieve competitive pricing and guarantee quality and standards of clean hydrogen supply.

With interest in hydrogen growing, such incentives are now being rolled out globally.

The landmark US Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) of 2022 includes a $3 tax credit per kilogramme of hydrogen produced by renewable sources, creating a powerful tailwind for hydrogen production. The EU’s REPowerEU scheme has committed to increasing hydrogen production by 10m tonnes per year within the EU and ensuring 10m tonnes of green hydrogen imports into the region by 2030. In Japan, a Green Innovation Fund is subsidising projects to develop large-scale supply chains of liquefied hydrogen. In June 2023, the Japanese government also revised its Basic Hydrogen Strategy, with a pledge to invest over ¥15tn ($101bn, 1 USD=148 JPY) in hydrogen together with the private sector in the next 15 years. It aims to increase the size of the domestic hydrogen market sixfold, increasing its production goal from 2m tonnes to 12m tonnes by the year 2040.

These measures need to be expanded and accelerated, explains Kanehana, for announced hydrogen projects to reach FID. Equally important, industry standards across the value chain will be required to enable safe and transparent global trade flows.

Pioneering a path in hydrogen innovation

Since first building a liquefied hydrogen rocket engine combustion test facility for Japan’s space program in 1978, Kawasaki has been a national pioneer of hydrogen technology. The company has been developing liquefiers, storage tanks, marine carriers and other technologies for producing, transporting, storing and utilising hydrogen. It has successfully demonstrated a liquefied hydrogen supply chain between Japan and Australia, working with governments and partner companies in recent years. In 2022, the Kawasaki-built ship Suiso Frontier became the world’s first liquefied hydrogen carrier to transport its cargo across continents successfully.

The company is now focused on expanding these technologies to achieve commercial feasibility. Such solutions will be increasingly vital in a world where global hydrogen flows will involve not just pipelines but also trans-continental shipments of hydrogen and its derivatives. Consultancy firm McKinsey estimates that, by the year 2050, more than 40 major trade routes will connect regions capable of cost-effective hydrogen production with the major demand hubs in Asia and Europe. These connections will be facilitated by marine transportation and by pipeline networks, respectively.

Anticipating this trend, Kawasaki has already begun discussions with various companies to create liquefied hydrogen supply chains worldwide. For example, in April 2023, the company signed a Strategic Collaboration Agreement with ADNOC, the UAE-based provider of lower-carbon intensity energy, to explore potential opportunities for the establishment of international liquefied hydrogen supply chains.

Creating a sustainable hydrogen ecosystem requires more than producing and delivering. There must also be long-term, committed demand driven by expanding hydrogen use. Here, too, Kawasaki is at the cutting edge of a range of end-use applications. These technologies encompass turbines designed for electricity and heat generation, offering exceptional fuel flexibility, enabling the utilisation of 100 per cent hydrogen, 100 per cent natural gas, or any mixture of the two.

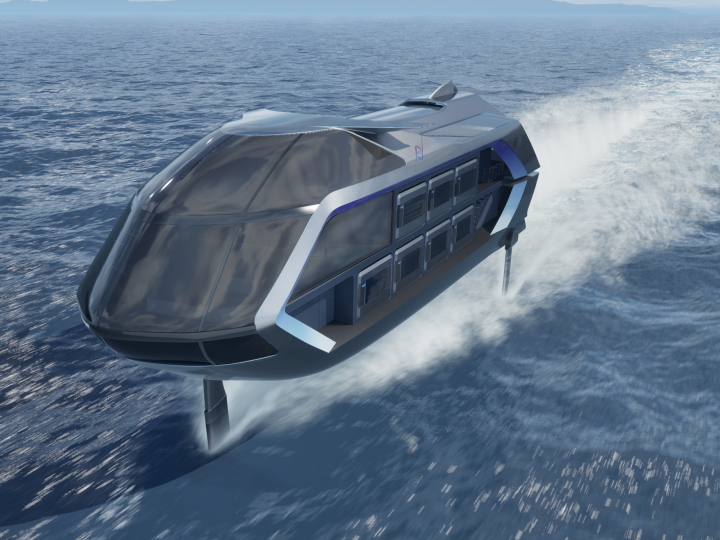

Kawasaki plans to conduct testing of a 30MW class hydrogen-ready gas turbine with German multinational energy corporation RWE, commencing in 2026. It is also developing hydrogen-powered engines and systems for ships and aviation, in partnership with other makers and with Japanese government funding.

Kanehana likes to compare the situation of the hydrogen sector today to the birth of the LNG market some fifty years ago.

He notes that Japanese companies took a leap into the unknown by investing substantially to create an LNG supply chain during that period, with the government choosing to back utility companies to build infrastructure and absorb the associated higher costs. Kawasaki contributed by building Asia’s first LNG carriers and subsequently many more. By providing the solutions to store and transport natural gas on ships, not just via pipelines, LNG imports became possible. This transition proved instrumental in helping Japan and other Asian nations meet rising energy demands, reduce their reliance on coal and combat issues related to smog and air pollution.

There are similarities between LNG and hydrogen in terms of supply chain know-how and infrastructure, and the recent success in transporting liquefied hydrogen by ship benefited from the technology and expertise developed for LNG. In the future, various applications now powered by natural gas will be powered by hydrogen, a clean energy source.

“Many voiced doubts when Kawasaki announced its future vision of marine transportation of liquefied hydrogen, regarding it as a fantasy,” says Kanehana. “But we went on anyway to develop necessary storage and shipping technologies beginning in 2010. Twelve years later, we had proven feasibility.”

Kanehana adds: “We believe our innovations can contribute greatly to the coming hydrogen transition, helping the planet achieve greater energy security and decarbonisation. Together with members of the Hydrogen Council and our colleagues from around the world, we aim to make hydrogen really take off.”

This content was paid for and produced by Kawasaki Heavy Industries in partnership with the Commercial Department of the Financial Times.